Public Spending and Financial Markets

How Much Should We Worry?

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

The great economist John Maynard Keynes explained that some public spending was necessary to stimulate growth, alongside a dynamic private sector. Despite much debate, this is still the dominant view globally among economists.[1]

Despite this, there is still a strong view, including among politicians and Treasury officials, that governments should seek equivalence, as rapidly as possible, between their overall spending and their overall revenue, from taxes or whatever. If public debt is "too high", then taxes must be increased, public spending reduced, or both.

Generally, Keynesians are critical of this view. In recent years a group of economists developing what they describe as Modern Monetary Theory, have refined these arguments. They rightly point out that a national economy with its own sovereign currency is not like a family or a business. Such an economy cannot go bankrupt. Money can be created “out of nothing” as Joseph Schumpeter once put it. Money can be created by public borrowing from individuals or banks, or from other corporations. The lenders are no poorer, because they hold IOUs from the government among their assets. But the government can spend extra money on public services.[2]

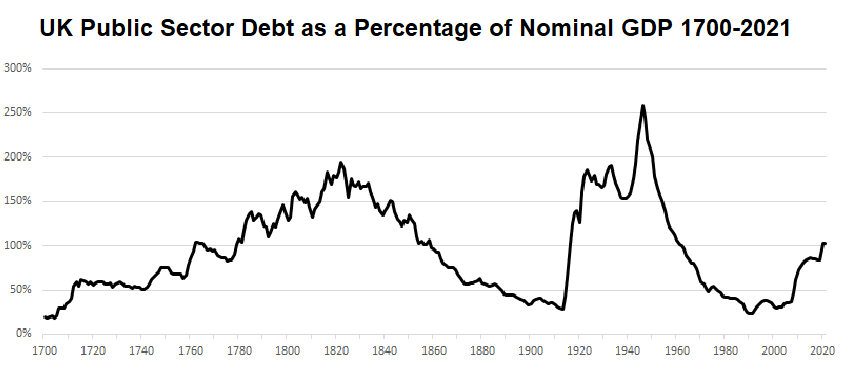

A prominent idea among politicians is that if a government runs up debt, then it must pay it off as quickly as possible. But historically this has never happened. UK public debt grew rapidly from 1700 as a result of several wars, and reached a peak of 194 per cent of GDP in 1822. The same years saw the Industrial Revolution. Private enterprise was not “crowded out” by public debt. On the contrary, public debt was a stimulant.

From 1822, UK public debt declined slowly until the outbreak of the First World War. Two World Wars brought it to the twentieth century peak of 259 per cent of GDP in 1946. It then declined, until the Great Crash of 2008 and the COVID pandemic from 2022. It is currently around 100 per cent of GDP. This is well below the levels of 1822 and 1946, so there should be no panic to bring it down.

Constraints on Public Spending

But as Modern Monetary Theorists and other Keynesians have made it repeatedly clear, this does not mean that there are no constraints on public spending. There are limits. The next – very important – question should be: what are these limits?

Following Keynes on this point in his How to Pay for the War, Modern Monetary Theorists argue that there is a limit when an economy is making full use of its resources, including of labour, capital goods, and materials. When that point is reached there is a danger of high inflation. Most developed economies, including the UK and the US, are not near that point. There is (hidden and officially recorded) unemployment and spare working capacity.

While Modern Monetary Theorists (MMT) are clear that we cannot “just print our way into prosperity” as Stephanie Kelton put it, a problem is that several of them seem to suggest that the full employment of resources constraint is the only important limit that we need to consider. There are several cases in MMT writings where problems of financial instability are recognized, but they are typically regarded as secondary or unbinding.[3]

On the contrary, there are other important constraints. These are political as well as economic in nature, and they can be immediate and powerful. One of them is sovereign currency devaluation, including speculation against it when the exchange rate is floating. Especially when they are prodded by an unsympathetic press, the markets can react against what is perceived as government “overspending”. To stress, I write “perceived” not “actual” overspending. Perception and truth are often different.

Is sovereign currency devaluation a problem?

If we look solely at the economic consequences, then currency devaluation can be beneficial. Exports can be boosted because they become cheaper for buyers abroad. Competitiveness is increased. Growth can result.

There are possible downsides, including import price inflation, an increase in any debt denominated in other currencies, and possible capital flight. Devaluation can be a temporary fix if structural and productivity problems are not alleviated.

But we can leave these economic pros and cons aside for a while. The primary and most immediate problem with currency devaluation is political. Consider two historical cases in the UK, under a Labour Government in 1967 and a Conservative Government in 2022.

In the 1960s, the UK currency was on a fixed rate against the US dollar and several other currencies. Currency devaluation was a political decision. To stimulate the flagging economy, Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson was under pressure to devalue the British Pound against the US Dollar. On 18 November 1967, Wilson announced the devaluation of the pound from $2.80 to $2.40 – a drop of 16.7%.

In economic terms this was probably a wise decision. The Pound was regarded as overvalued. But in political terms it proved disastrous for the government.

A tale of two crises

From August to October 1967 inclusive, Labour was polling an average of about 41%. Except for one poll (of 38% in October 1967) it had consistently polled above 40% since the 1966 election. Labour support fell substantially after the devaluation. One poll gave Labour 32% in December 1967. Average Labour polling for the first six months of 1968 was 32%. Labour in all likelihood lost over 8 percentage points because of the devaluation. Labour clawed back some support in late 1969, moving back above 40% again in October. But Labour lost the June 1970 election, when it received 43% of the vote and the Conservatives 46%. Labour fell from power.

Wilson had tried to persuade the public of the need for a devaluation with the (false) narrative that the “pound in your pocket” would not change value. It did, at least when you went abroad or purchased the same imports as previously. But the most important point is that people (rightly or wrongly) entrust governments to keep the currency stable. A currency devaluation undermines that trust and encourages perceptions of incompetence. If many leading economics had argued that the devaluation would be beneficial, then there is no guarantee that public opinion would have been very different. And in a democracy, public opinion (misguided or otherwise) matters.

My second example is from 2022, during a period of Conservative rule dating back to 2010. For just over 50 years the British Pound had floated on the international currency markets. On 6 September 2022, Liz Truss became UK Prime Minister. Kwasi Kwarteng was her Chancellor. On 23 September Kwasi Kwarteng announced his radical budget, involving cuts in both public spending and taxes. The net result would have been an increase in public borrowing. The Pound began to fall rapidly against the US dollar. By 26 September the Pound had fallen to an all-time low of $1.0327. This was a drop of 11% in 11 days since 12 September. This is the fastest substantial fall (say of 5% or more) of the British Pound in its history.

Truss tried to rescue the situation by reversing some of the tax cuts and sacking her Chancellor. But these measures were too late. Her personal popularity levels plummeted to record lows for a British Prime Minister. After a period of political turbulence and extraordinary volatility on the financial markets, Truss resigned on 20 October. Without a general election, a new Conservative government was formed under Rishi Sunak. The Conservatives did not recover from this financial instability and perceived incompetence. They were soundly defeated by Labour in the 2024 General Election.

One message here is that public perceptions are important. Whatever the economic value of a currency devaluation, the public see them as incompetent betrayals of the trust in the government to maintain a sound currency. Hence currency devaluations are unpopular. Few elected governments can withstand the political shock of a substantial and rapid fall in its currency.

Conclusion

Similar arguments can be made about falls in the financial markets for stocks or bonds. Whatever their economic effects, people regard them as signs of economic weakness or political incompetence. This too, in a democratic country, is another political constraint on the growth or extent of public debt.

We need to increase public expenditure, and not necessarily alongside increases in corresponding government revenues. But all this needs to be done carefully, by politicians that can appeal to the public, and with an eye to calming the financial markets. Like it or not, that is the nature of the world in which we live. There are both economic and political constraints. Both have to be taken into account.

Endnotes

1. Keynes (1936). A recent global survey of 1713 academic economists, with over half with PhDs from the US, found that 76 per cent agreed (strongly or otherwise) that “fiscal policy has a significant stimulative impact on a less than fully employed economy.” A majority of 56 per cent disagreed (strongly or otherwise) that “government interference in the economy should be minimal, leaving as much as possible to private enterprise and markets”. A paper reporting this survey is in preparation for publication, by the present author and three others.

2. Schumpeter (1934, p. 73), On Modern Monetary Theory see for example, Wray (2012, 2018), Kelton 2020), and Keen (2022).

3. Wray (2018, p. 81), Kelton (2022, pp. 37-41).

References

Keen, Steve (2022) The New Economics: A Manifesto

(Cambridge UK and Medford MA: Polity).

Kelton, Stephanie (2020) The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and How to Build a Better Economy

(London: John Murray).

Keynes, John Maynard (1936) The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money

(London: Macmillan).

Keynes, John Maynard (1940) How to Pay for the War

(London: Macmillan).

Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1934) The Theory of Economic Development: An Inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest, and the Business Cycle (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press).

Wray, L. Randall (1998) Understanding Modern Money: The Key to Full Employment and Price Stability

(Cheltenham and Lyme, NH: Edward Elgar).

Wray, L. Randall (2012) Modern Money Theory: A Primer on Macroeconomics for Sovereign Monetary Systems

(London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan).

First published 19 October 2025