Public debt and inflation: What is to be done?

Should governments, at least in the long run, ensure a balance between their income and their expenditure? Surely, this is a simple matter of fiscal responsibility? Running deficits will lead to damaging inflation. Or so we are told.

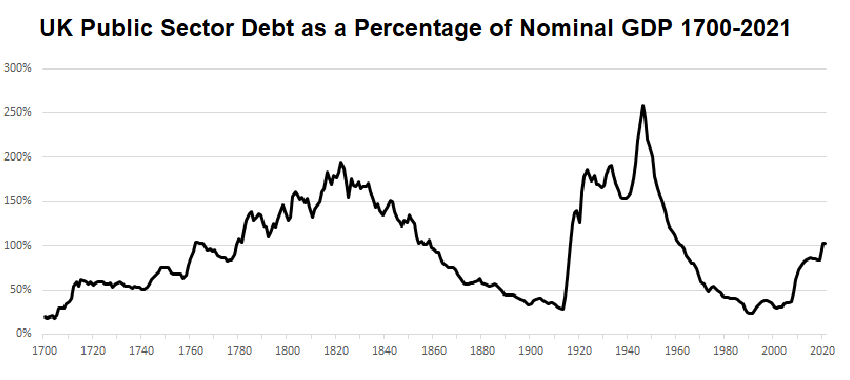

Was inflation a problem in those years? We have data for inflation rates from 1751 onwards. Annual inflation rates were volatile in the eighteenth century. High points were reached, but inflation sometimes went negative. The average annual rate of inflation from 1751 to 1822, in a period when public debt was soaring, was only 1.1 per cent. Decades of public debt levels of well over 100 per cent of GDP did not lead to sustained inflation.

The latter half of the eighteenth century saw waves of innovation and the rise of industry. High public spending and debt did not ‘crowd out’ private industrial investment in that period. On the contrary, the economists Jaume Ventura and Hans-Joachim Voth have argued that ‘sovereign debt accelerated the first Industrial Revolution’.

The high levels of public debt did not burden the coming generations, as many politicians have warned us. The expansion of the economy through the nineteenth century ensured that the national debt could gradually be paid off, without depressing living standards. Debt had helped to stimulate growth. Economic expansion provided the means of repaying debt, without lowering living standards.

In the twentieth century, involvement in the First World War led to a huge surge in UK public debt. In 1919, when the war had ended, the debt had reached 140 per cent of GDP. But economic growth was then lacking in the UK. Mass unemployment increased and the 1930s saw the Great Depression. UK public debt remained well above 100 per cent of GDP throughout the interwar period. From 1915 to 1918 inflation had leapt upwards, peaking at 25 per cent in 1917. But average inflation for 1919 to 1939 was negative, at -0.5 per cent.

The Second World War saw an historically unprecedented surge in UK public debt, reaching an all-time high of 259 per cent of GDP in 1946. But the UK economy then began to grow, enabling once again a steady reduction in public debt. In 1963 the debt fell below 100 per cent of GDP and stayed below that value until 2020. In the years from 1946 to 1962 inclusive, when the debt was above 100 per cent of GDP, inflation averaged 4.3 per cent.

Overall, the UK economy has suffered from several bouts of inflation in excess of 10 per cent. But it is difficult to blame these largely on public debt. Inflation occurs for additional and more important reasons. There is no close correlation between public debt and inflation.

The Great Crash, Covid and Brexit

After the Great Crash of 2008, an increase in public debt was necessary to prevent a banking collapse. This surge is shown in the above Figure. From 2010 to 2015 the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats formed a coalition government that began to implement austerity measures. The reduction of public debt was mistakenly prioritized, and several departmental budgets were dramatically reduced. Public services and living standards suffered. Conservative governments from 2015 have continued with similar priorities and efforts.

But austerity programmes have not been successful in reducing public debt. On the contrary, its percentage of GDP has increased from 72 percent of GDP in 2010 to 103 percent in 2021. Austerity has failed in its own terms. The economic damage has included a major erosion of important services, including education, health, policing and defence. Austerity is a misconceived and destructive policy.

The Covid pandemic led to another increase in the public debt. The first year of the pandemic – 2020 – coincided with the UK exit from the European Union (EU). Both these events had profound negative effects on the UK economy. Economic growth was not available as a means to gradually reduce public debt, as it had been in the nineteenth century and after 1945.

The combination of a hard Brexit, and the energy crisis resulting in part from the war in Ukraine, have led to a dramatic rise in the UK rate of inflation in 2022. A hard Brexit, with its curtailment of free movement, has exacerbated labour shortages in several sectors. The UK has an alarming deficit of skilled labour. This is an era not of mass unemployment, but of labour deficits. The problem could have been alleviated by government-funded skill training. But these training budgets are severely inadequate and have suffered because of austerity.

Labour shortages and inflation are precisely the conditions that Keynesians identify as placing limits on the use of public spending to stimulate the economy. We cannot rely on monetary issue alone. The problem of inflation has to be addressed. Some rapidly acting measures are required to bring inflation down.

Inflation: what is (not) to be done?

This is not the time to prioritize tax cuts. Cutting taxes will increase disposable income. This would raise effective demand and inflationary pressure. Instead, with rising economic inequality, taxes should rise for the rich. In these difficult times the rich should pay more to help.

Contrary to Tory Party mythology, no modern complex economy can function with low taxes and a small state. This is not the nineteenth century. In modern economies, lower taxes do not lead to sustainable economic growth. The highest performing developed economies have strong welfare states.[3]

Although it was not stated on the 2016 ballot, the UK ended up with a version of hard Brexit that meant it left the EU Single Market and Customs Union. Other countries, including Norway, Switzerland and Iceland are not EU members, but they have full and low-cost access to the EU Single Market. They are not encumbered by the self-imposed red tape on exports that has had a devastating impact on UK businesses. Although other factors are involved, the UK’s hard Brexit is a major cause of the recent rise in inflation.

It is highly unlikely that circumstances will arise within a decade that will allow the UK to re-establish its membership of the European Union. In the next few years it would be more feasible to follow Norway and others by establishing a much closer relationship with the EU Single Market. This needs to be done as quickly as possible. It would reduce one of the major inflation pressures and to repair some of the serious damage to the UK economy.

While official unemployment figures are relatively low, the deficit of skilled labour could in large part be alleviated by an emergency retraining programme to bring more people into the skilled workforce. To alleviate acute shortages, arrangements could be made to allow more EU nationals to work in the UK economy. The problem of low productivity in the UK economy needs to be addressed. Increasing productivity can lower costs and reduce inflationary pressure.

These are a few of the measures to be considered to reduce inflation pressure and to stop a rising spiral of prices and wage demands. In addition, the government has to deal with other urgent issues, including the climate emergency, the cost-of-living crisis, and the decline of public services.

This article focuses on the issues of public debt and inflation. Neither tax cuts nor austerity are solutions. We should abandon the flawed economic assumptions and misguided policies that have prevailed in the UK for more than a decade.

11 July 2022

Minor edits: 19 July, 12 August, 12, 19 October 2022.

Endnotes

1. Bank of England data from https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PSDOTUKA and https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/governmentpublicsectorandtaxes/publicspending/bulletins/ukgovernmentdebtanddeficitforeurostatmaast/december2021.

2. See Hodgson (2023) for a discussion of this historical period.

3. See Kenworthy (2019) and Hodgson (2019).

Bibliography

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2019) Is Socialism Feasible? Towards an Alternative Future (Cheltenham UK and Northampton MA: Edward Elgar).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2023) The Wealth of a Nation: Institutional Foundations of English Capitalism (Princeton: Princeton University Press), forthcoming.

Keen, Steve (2022) The New Economics: A Manifesto (Cambridge UK and Medford MA: Polity).

Kelton, Stephanie (2020) The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and How to Build a Better Economy (London: Murray).

Kenworthy, Lane (2019) Social Democratic Capitalism (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press).

Keynes, John Maynard (1936)

The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (London: Macmillan).

Keynes, John Maynard (1940) How to Pay for the War (London: Macmillan).

UK Office of National Statistics, inflation data available at https://www.in2013dollars.com/UK-inflation.

Ventura, Jaume and Voth, Hans-Joachim (2015) ‘Debt into Growth: How Sovereign Debt Accelerated the First Industrial Revolution’, NBER Working Paper 21280, National Bureau for Economic Research, Cambridge MA.

Wray, L. Randall (2012) Modern Money Theory: A Primer on Macroeconomics for Sovereign Monetary Systems (London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan).